Later that same day ...

7 September 2020

You may have seen this press release from RenewableUK in late August 2020.

It reports a new record for wind power, generating 60% of Britain's electricity at 01.30 on 26 August 2020.

On the face of it this seems like really good news. But maybe the folks at RenewableUK should have kept an eye on the grid just a little longer.

Later on during the very same day the wind dropped and on both 26 and 27 August 2020 coal was supplying more electricity to the National Grid than wind was - and that's the total for onshore and offshore wind.

Yes - that's right - coal.

The intermittency of wind is a common problem. Note how RenewableUK did not report on wind's poor performance on Global Wind Day this year.

But few days have demonstrated the scale of the problem more clearly than 26 August 2020.

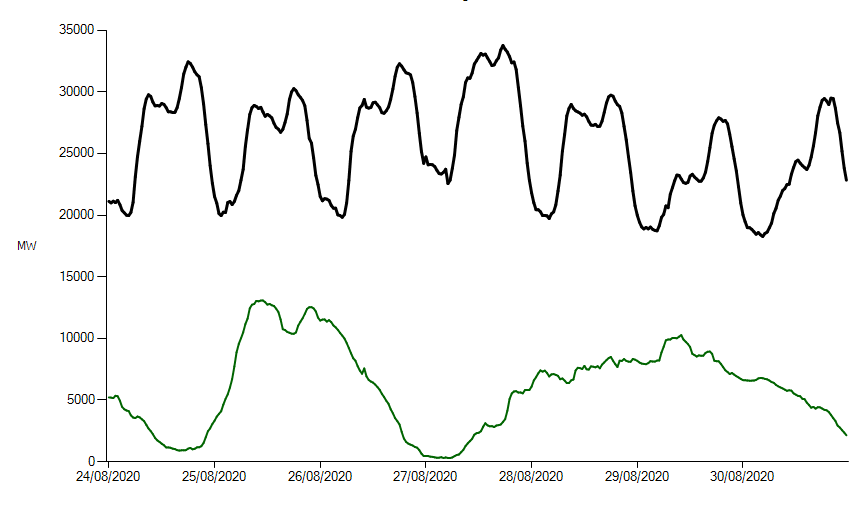

The upper line in the graph shows demand during week commencing 24 Aug 2020. The lower line shows the performance of wind. Note that when the wind was at its lowest CCGT gas filled as much of the gap as it could, but sometimes even gas couldn't do enough, so coal was brought online.

As GB electricity demand increases - which it is expected to do - and the amount of wind power that is used increases, the gaps between demand and the worst wind performance will get greater and greater. Even with the current reduced levels of demand you can see from the above graph that there were times when demand was over 30GW but wind was producing barely 1GW or even less.

Yet there is no quantified plan to be able to deal with these shortages of supply.

Based on the latest National Energy System Operator FES documents here., peak demand could exceed 70GW by 2050 and with wind and solar comprising well over 50% of available capacity, on a winter evening in a wind lull the shortfall could easily be well over 40GW, or even more. Coal is forecast to have gone altogether, and the use of CCGT gas will have diminished.

Even if the maximum power available from interconnectors - a little over 27GW (and we cannot guarantee that this will be available to us) - is available, the expected amount of storage available would only last an hour or two, even if it's fully charged before the wind lull begins.

Other approaches are planned for the future, but they are largely unproven at scale.

But we still have no quantified calculation from RenewableUK, the National Grid - or anybody else for that matter - that explains how this level of extreme intermittency - which is not at all rare - is going to be dealt with.

So, how is it going to be dealt with?